|

|

|

|

The Tempest

|

|

|

November 2000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

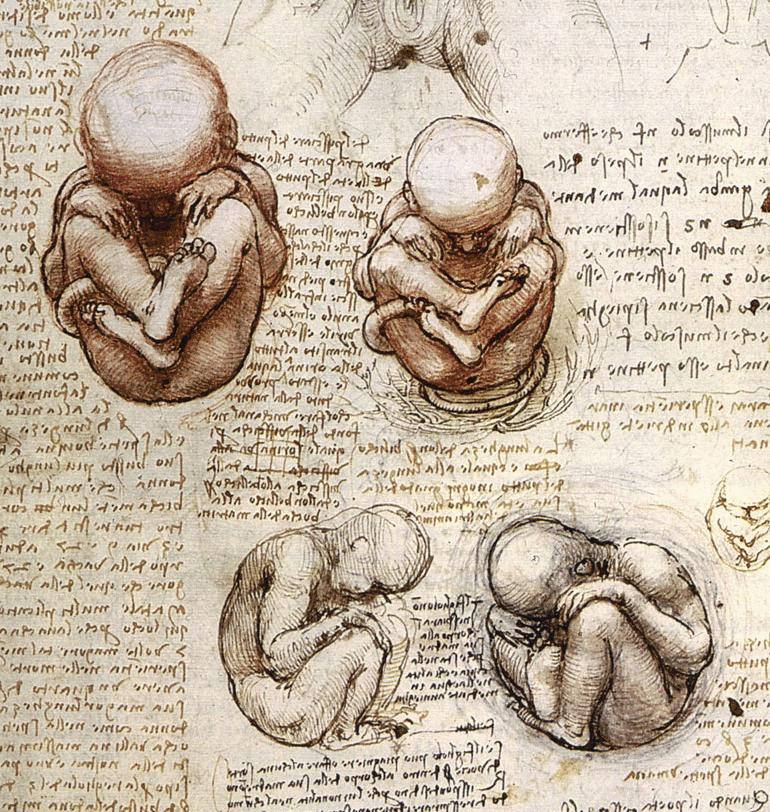

The Tempest is very much a play of the Renaissance. In it we see the chief character, Prospero, as a man of immense learning

in both the arts and sciences before their (temporary?) split into two separate disciplines. In many ways Prospero is a bit

like a Leonardo da Vinci, a profoundly gifted scholar who massively influenced the developments of modern science. In our

production we draw upon the curious parallel that Leonardo spent long years in the service of duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza

after writing to him telling him of his engineering abilities including knowing how to build portable bridges, construct state-of-the-art

war machines, sculpt in a variety of media and was a brilliant architect. During the years with the Duke of Milan, Leonardo

produced several paintings and was commissioned to many enterprises, not many of which have survived or came to fruition.

He never completed his scientific or artistic vision. Much of Leonardo's legacy is in the form of his plans in detailed

notebooks. Shakespeare couldnt have known much of this as the notebooks were not published in his lifetime. In December

1499, however, the Sforza family was driven from Milan by French forces and Leonardo had to leave to return to Florence.

The play begins with Prospero's long tale of how he served as Duke of Milan but became too distracted and consumed by his

intellectual curiosity and left the management of the affairs of state to his brother. Who promptly betrayed him and ran

him out of town.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

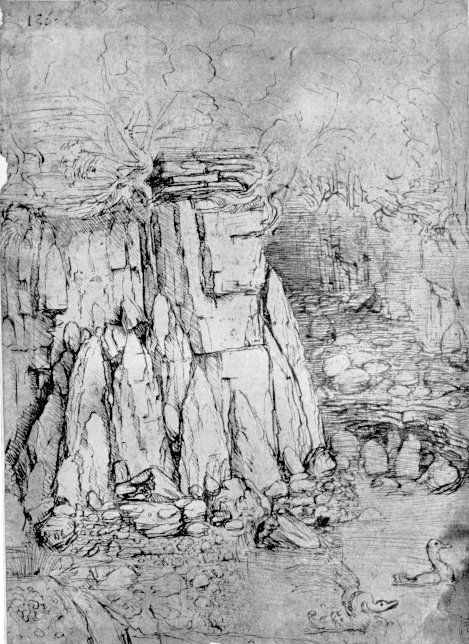

What both stories reveal is that the time was a period of tremendous curiosity, the New World was being discovered or colonised.

Tales from sea travellers revealed islands with strange characters and customs, savages and cannibals or noble, generous

creatures. Shakespeare forces us to consider issues like nature versus nurture in The Tempest and the purposes and value

of education and learning. Shakespeare had already written his great tragedies when he came to write The Tempest. His extraordinary

insights into psychology which he demonstrates in Hamlet or Macbeth is still a part of The Tempest but he seems more interested

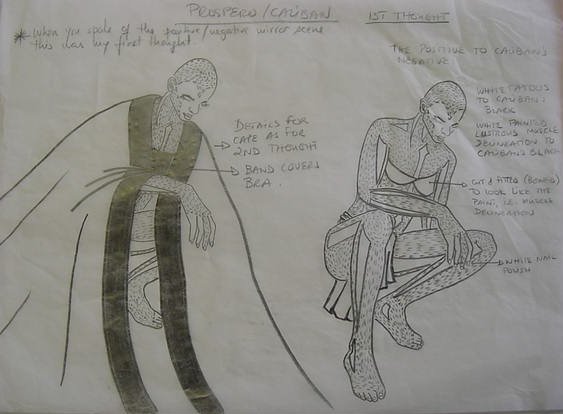

in storytelling or myth and the unconscious. The casting of Francine Watson and Simon Watson, brother and sister, as Prospero

and Caliban respectively lends our production a darker and mysterious quality.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Tempest can also be seen as a revenge play. Prospero is bent on getting his own back after being deposed by his brother,

Antonio. He takes it very personally (as well he might!) and is terribly wounded psychologically. When he gets the opportunity

to plunge his enemy Alonso, King of Naples, who has aided Antonio, he doesn't hesitate. He punishes him ruthlessly, plunging

Alonso into torment and anguish by allowing Alonso to believe that his son is dead. Prospero is very austere in his treatment

of Ferdinand, the Kings son, and merciless in his control over Caliban, his slave, and Ariel his tricksy spirit. But Prospero's

purpose is benevolent ultimately and herein lies the interest of the play. Prospero has been blind to the responsibilities

which come as minister of state. His learning has been self-serving and he has tremendous powers. He says he can "call

forth the mutinous winds" and set "roaring war" between the sea and the sky. "Graves at my command/have

waked their sleepers oped and let em forth" he continues.

But these powers have manifested themselves in tricks and quaint devices such as making banquets out of thin air and making

them disappear again, causing hallucinations and illusions of shipwrecks, all with the aid of his Ariel He decides to renounce

his magic by the end of the play in favour of genuine wisdom and intends to return to Milan to resume his duties. In breaking

his staff and burying his books, Prospero questions the nature of learning and responsibility. So what begins as punishment

and revenge ends with reconciliation and redemption through forgiveness.

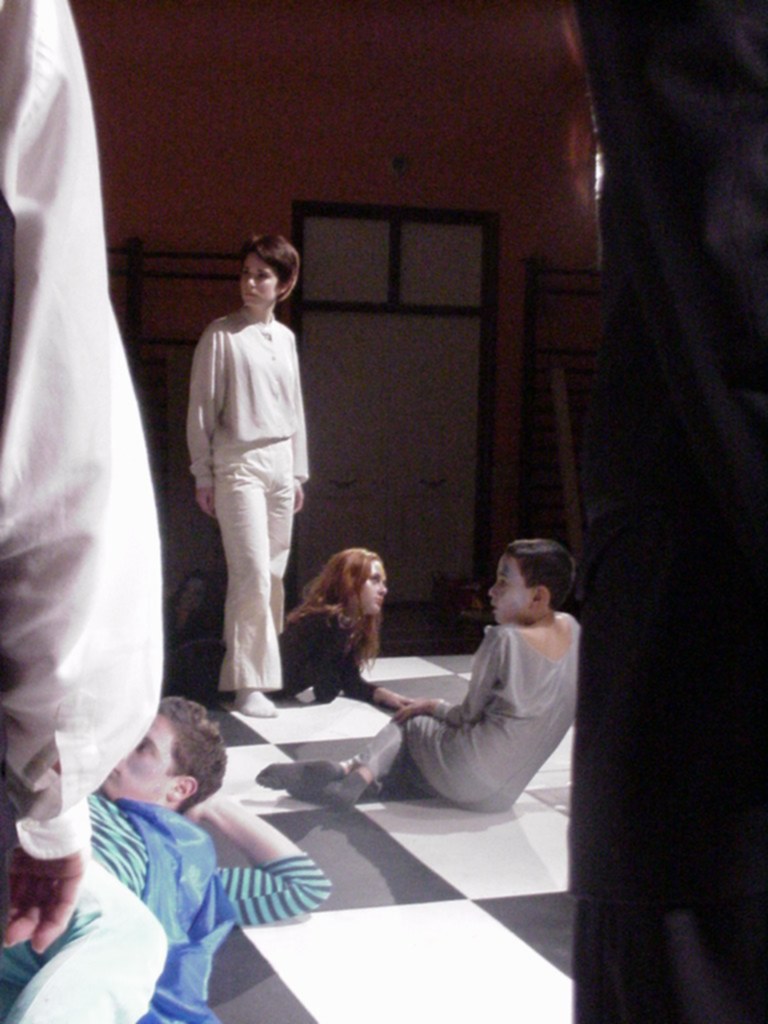

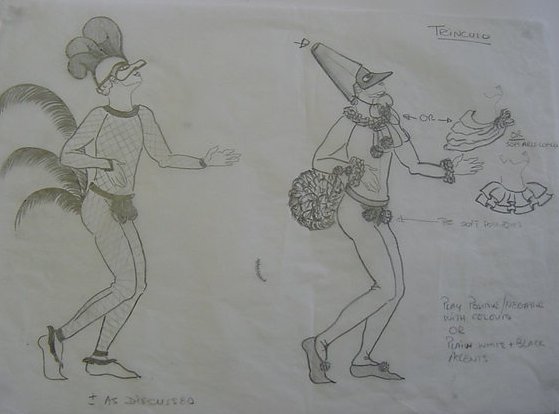

It's worth making a couple of points about casting. In deciding to do another Shakespeare a teacher has to confront the obvious

problem of gender There are very few female parts in his plays. As we all know women were not allowed to perform on stage

in Shakespeare's day and so young boys played the parts of women Many of Shakespeare's plays makes reference to this and

much humour and interest comes of his questioning of gender roles. Following the lead of the RSC who cast Mark Rylance last

year as Cleopatra and Vanessa Redgrave as Prospero, I decided to dispense with convention and have cast many young women in

central male roles. This has produced some interesting and lively workshops in rehearsal and will certainly give cause for

reflection on the part of the audience. As for the unusual casting of Ariel as a multiple spirit I wanted to allow the opportunity

for some of our very talented young actors to explore aspects of performance different from straight roles. When he first

appears, Ariel announces himself as "Ariel and all his qualities" and speaks of his ability to divide and appear

in many places at once. In this way we see Ariel as a complex personality with competing drives and moods and allows us to

be transported further into the magical world of Shakespeares imagination.

|

|